Chess variants, and my own handmade chess set

A Brief History

Chess, one of the most popular board games ever invented. An ancient game with a storied history. It was one of the first games to feature units that moved differently, and when you think about it, one of the first tabletop wargames. When it was first invented in India, the game was called Chaturanga, which is Sanskrit for "four sides", referring to the four branches of the Indian military. These four branches were:

- the infantry, represented in the pawns

- the cavalry, represented in the knights

- the elephants, which later became the bishops

- the chariots, which later became castle-shaped pieces called rooks

The last two pieces were the king, of course, but not the queen. Instead, the king was accompanied by a "ferz", or advisor, who was the weakest piece, only able to step one square diagonally. When Europeans came to India and the Middle East, they brought early versions of chess back with them, which they learned from the locals. From there, the ferz became more and more powerful, until it became the queen we know today.

Orthodox Chess

It'd be a bit inaccurate to call this "original", "regular", "normal" or "vanilla", given the rich history and many changes that made the game what it is today. The term that the Chess Variant Pages use is "Orthodox Chess", so that's what I'll use here. Nonetheless, Orthodox Chess is the most common version of chess, the kind you'd be playing with a generic set you bought at the store.

The objective of Orthodox Chess is simple. You must threaten your opponent's king with capture, in such a way that they are unable to escape the threat. A state like this is called "checkmate."

Orthodox Chess features two symmetrical armies: one white, and one black. Each player starts the game with one king, one queen, two bishops, two knights, two rooks and eight pawns. The board itself is an 8x8 square of tiles, arranged in alternating colors. When setting it up, the board is ALWAYS positioned such that a light-colored square is in the rightmost corner square in front of each player. (Since the board is rotationally symmetrical, both players will have a light square on their right.)

In this chess set, blue pieces represent White, and red pieces represent Black. Rooks go in the corners, then the knights go next to the rooks, then the bishops. The queen always goes on the square matching her own color (i.e. White's queen will go on a light square, and Black's queen will go on a dark square), and the king always goes on the square opposite his color. From White's perspective, the queens start the game on the left side of the board, and the kings on the right.

White (or in this case, Blue) is always the first player to make a move. After that, Black makes their first move, and from there, White and Black each take turns, moving one piece at a time.

The King

The King is the ultimate objective of chess. His safety is paramount, and his subjects will lay down their lives to ensure it. Despite the considerable power such a high level of importance would entail, the King is actually not very mobile. He can move one square in any direction. When he is on an empty board, this gives him a maximum of eight squares to control. Because the King's safety is so important, the opposing player must give a warning before actually making an attempt on his life. When a piece threatens the King, your opponent must announce the threat by calling out, "Check." When your King is in check, you MUST escape the threat in any way possible. Inability to do so is referred to as "checkmate," and the game ends in a defeat for the player who is checkmated. Additionally, the King does not take kindly to treason, and is very much not suicidal. Therefore, it is illegal to move into check voluntarily.

The Queen

The Queen is the raw essence of "girl power." You could open the dictionary to the word "girlboss" and the definition would just be a picture of her. She is the most powerful piece on the board, several orders of magnitude beyond her husband. The Queen has the ability to move in any direction, as many squares as she likes. This might make it seem like a good idea to get her out ASAP, and to use her for everything, but that's not necessarily the case! Remember, you only start with one Queen per game, and due to her power, she's a very high-value target, and getting another one is very difficult! (But not impossible, see the section on Pawns below.)

The Rook

The Rook's name comes from the Persian word "rukh", which means "chariot." In ancient times, the Rook was depicted as a chariot, but when the game came to Europe (specifically, to Italy), it began being depicted as a tower. This design remained in use, and in modern chess sets, has become the standard look of this piece. As such, this is the design used for them here. Rooks move any number of squares forward, backward or sideways, but never diagonally. (Incidentally, on a completely empty board, a Rook will always have exactly 14 squares to which it can move.) The Rook also shares a special move with the King, known as "castling." To castle, the King and the Rook that will be participating must not have been moved before. (Even if you move them back to where they started.) The King moves two squares towards the Rook, and then the Rook jumps over the King to the next available square. This move cannot cause the King to move into check, out of check, or through check (i.e. the Rook cannot be under threat of capture when the move ends). Additionally, all squares between the King and Rook must be vacant in order for castling to be possible. Castling can occur in either direction, with either Rook. The advantages of castling are twofold: the King is placed in a corner square, out of harm's way, and the Rook is brought closer to the center of the board, where it can more easily launch powerful long-range attacks.

The Bishop

The Bishop's most notable feature is his tall, double-pointed hat. A hat in this style is called a "miter." The Bishops serve as the King's most trusted advisors, and as such, they begin the game directly surrounding the King and Queen. The Bishop's movement pattern, just like his religious symbol of choice, looks like a cross. Bishops can move diagonally, for as many squares as they desire. Uniquely, this means that they are color-bound; the color of square on which they start is the color on which they will stay for the entirety of the game. The two Bishops of each side each control half of the squares, never obstructing the movement of one another. (Almost never; see the section on Pawns below for details.)

The Knight

The Knight is a very unusual chess piece. In a normal chess set (read: not one stylized like the one shown here), he almost invariably has the most detailed shape of them all, looking like an actual horse, rather than the simplistic, peg-shaped designs of the other pieces. He also has the only movement pattern that doesn't go in a straight line. The Knight has the ability to move two squares in one orthogonal direction, and then one square perpendicular to the first direction. This method of movement, while convoluted, also has another stipulation that makes it a little easier: rather than taking an actual path to the square he's moving to, the Knight teleports directly to its new square, allowing it to pass through other pieces, as if they didn't even exist. A popular chess puzzle is the Knight's Tour: can you place a knight anywhere on an empty chessboard, then find a path of only knight moves that will take that knight to every square on the board exactly once?

The Pawn

The Red-Shirts. The Stormtroopers. The NPCs. The Mooks. Whatever you call them, such is the life of a Pawn, doomed to just be another expendable minion for the war their kings roped them into. Legend has it that two Pawns facing each other will be immobilized not because there's another piece in their way, but because they look each other in the eye, and they see someone who, maybe, just maybe, isn't all that different from them. Someone who, under different circumstances, might have even been a good friend or a valuable ally. They see themselves in each other, and it gives them pause, forces them to hesitate and introspect about the atrocities they have committed to get to the place they're in. Pawns are as numerous as they are weak. They can only step one square forward at a time. Never backwards, never sideways, never more than one square. There are exactly two exceptions. The first exception is that Pawns that have not been moved yet, fresh out of training and eager to show off their stepping-one-square abilities, sometimes get a little too excited and step forward by TWO squares. The second exception is that they cannot capture in the same way. Instead, the Pawn must capture with a diagonally forward step. The Pawn cannot step diagonally at any other time. The last thing to know about Pawns is that they do the things they do for exactly one reason: they desire to climb the social ladder. A Pawn that reaches the opposite end of the board (thus preventing them from performing any more forward steps) finally achieves their ultimate goal: to promote into a more powerful piece. Usually, this will be a Queen, but players also have the option to promote their Pawn into any other piece that is not a King. This is the only way to get more than one Queen, or to have two Bishops that both move along the same color of square.

Some Terminology on Chess Variants

The world of chess variants is vast, and it has a lot of different things to keep track of. To keep things standardized, players of chess variants have certain terminology that they use to refer to recurring elements in chess variant design. A few examples can be found below.

- Rider: A rider is any piece that may repeat its move any number of times in a single turn, so long as it does not move through an occupied square. The Rook, Bishop and Queen are all rider pieces, with the moves being repeated being a single orthogonal, diagonal or radial step, respectively.

- (X, Y) leap: When a piece makes an (X, Y) leap, they move X squares in one orthogonal direction, and Y squares in another direction, perpendicular to the first, passing through any other piece on their journey. (Due to the properties of the Cartesian plane upon which chess is played, an (X, Y) leap is also indistinguishable from a (Y, X) leap.) This is a generalization of the Knight's movement, which itself is described in this manner as a (2, 1) leap.

Meet the New Pieces

To better organize the pieces in my collection, I'll be sorting them into categories based on the variants from which they originate.

Capablanca Chess

The Archbishop

The Archbishop is a fusion piece that's probably best known for being from the Capablanca Chess variant. In some variants, it's known as a Princess (keeping the theme of fusion pieces being female) or a Paladin (sharing the religious theme of the Bishop and the warrior theme of the Knight) or a Cardinal (since it outranks a Bishop). Being a fusion piece, the Archbishop combines the movement of the Bishop with that of the Knight. This movement pattern gives the Archbishop the distinction of being one of the few pieces that can singlehandedly checkmate a bare King unprotected.

The Chancellor

The other piece that Capablanca Chess features is the Chancellor, another fusion piece. In other variants, it is sometimes called a Marshall or an Empress (though, this one is controversial, since it would imply that it's stronger than the Queen when it really isn't). I wasn't sure what a chancellor looks like, so I just made these guys Vikings. In the same way the Archbishop combines the powers of the Bishop and Knight, the Chancellor combines the powers of the Rook and Knight.

Xiangqi, a.k.a. Chinese Chess

The Cannon

In Chinese, this piece is known as the Pao (砲 for Black, and 炮 for Red, though the name is homophonous for both pieces), which is awfully appropriate since it sounds like the deafening "POW!" of a cannon being fired. Due to being a ranged piece, the Cannon has a unique restriction that the other pieces don't have. It can move as normal, but in order to capture, there must be a third piece, known as a "screen", in between the Cannon and its target. The Cannon jumps over the screen and lands on the target to capture it. It must jump over exactly one piece, and it may not jump if a capture will not result from that jump.

Gross Chess

The Archer

This piece is analogous to the Cannon, and in actual Gross Chess, it is known as a Vao (pronounced like "vow"). The name is intended to evoke a similar feel to the word "Pao", but ultimately it is entirely fake. It does not come from a Chinese word, and in fact, Chinese doesn't even have the /v/ sound in its phonetic inventory. Another name for the piece is the Canon (with only one N, not two), a type of cleric. Ultimately, when I created my chess set, I decided to make this piece an Archer, to keep the theme of ranged weaponry. The Archer has the same "must jump over a screen to capture" limitation as the Cannon, but instead it moves like a Bishop.

Omega Chess

The Wizard

The Wizard is a color-bound piece intended to be analogous to the Bishop. It can either step one square diagonally, or it can make a (3, 1) leap.

The Champion

Both the Champion and Wizard have movement patterns that control up to 12 squares. The Wizard's squares of choice are more spread out, but the Champion's squares are better for close-range combat, being more densely packed. The Champion can either step one square orthogonally or jump exactly two squares orthogonally or diagonally.

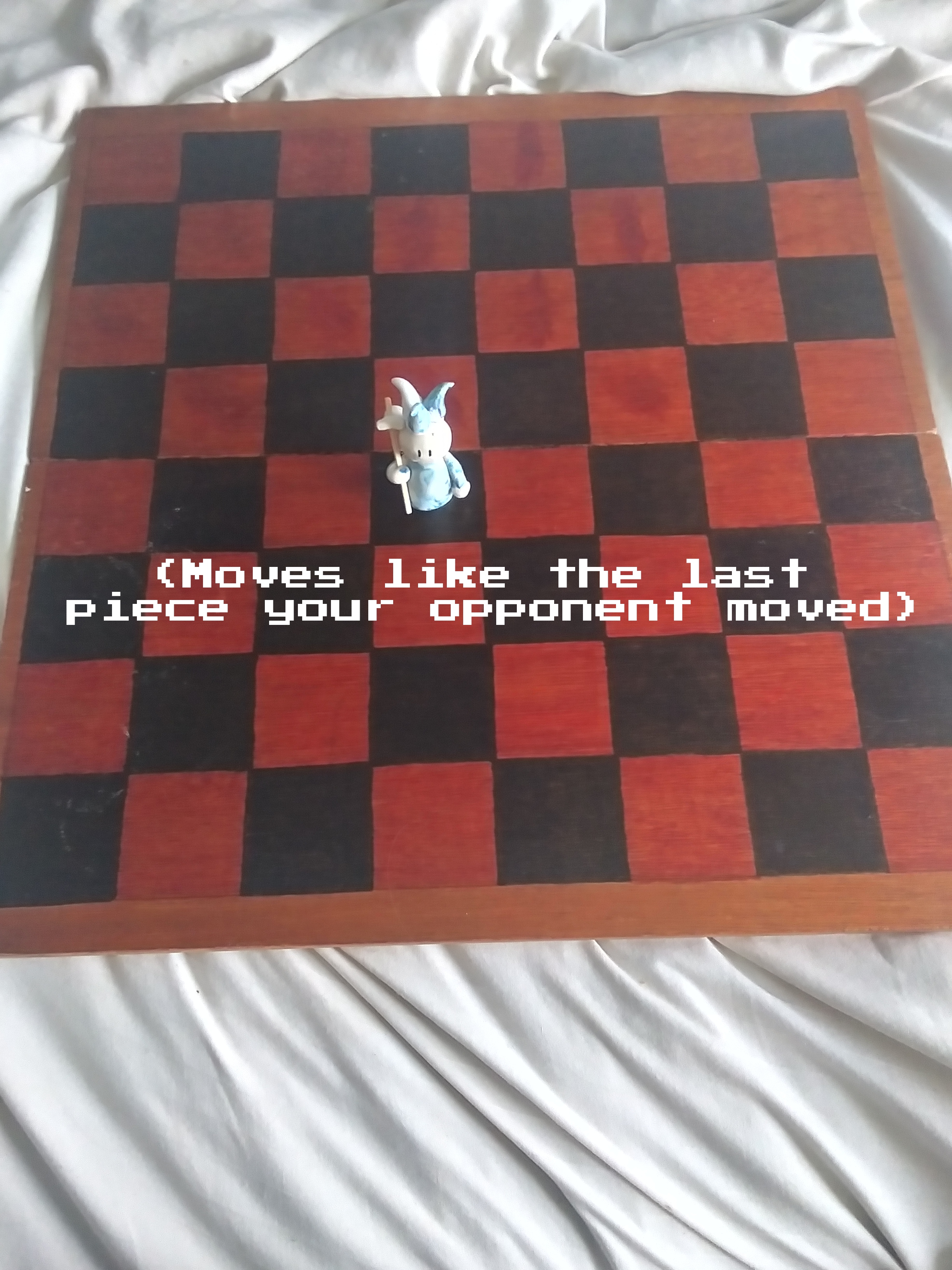

The Fool

Like many clowns found in games, the Fool is a wildcard character. His specialty is mimicry, being able to move like the last piece your opponent moved. However, the Fool doesn't start on the board like a normal piece, because that would just be boring. Instead, the Fool waits for another piece to either make their first move, or make a capture, at which point the Fool makes a dramatic entrance, being dropped onto the board into the newly-empty square from which that piece just moved. I wasn't sure whether I wanted to have the Fool look like a literal fool or the man on the Fool tarot card, so I did both, by giving him both a bindle and a cockscomb cap.

Musketeer Chess

(Disclaimer: These pictures were taken during a move. I didn't have my usual poker chips on hand, so I used BakuCores instead.)

The Leopard

The Leopard is effectively a weaker Archbishop, sharing all of its Knight movement, but only being able to slide up to two squares diagonally.

The Fortress

The Fortress has the ability to slide up to three squares diagonally, or jump exactly two squares orthogonally, or make a (2, 1) leap, with the exception that the two-square part of the leap must be vertical.

The Hawk

The Hawk, being a bird, has a movement pattern consisting only of jumps. It jumps either exactly two or exactly three squares, orthogonally or diagonally.

The Spider

The Spider... actually isn't a spider, not even in an official Musketeer Chess set. It's only called that because its movement pattern looks like a spider web. The Spider can either slide up to two squares diagonally, or make a (2, 1) leap, or jump exactly two squares orthogonally.

Old versions of orthodox chess pieces

The Dragon

What would a game about fantasy warfare be without dragons? This piece was also one of the steps on the Queen's rise to power, and is also called the Amazon, the Terror, or the General, but come on, it's a DRAGON. How much cooler can you get?! Anyway, the Dragon is a piece with FORMIDABLE levels of power. I guess it was too much for early versions of chess to handle, since it got nerfed down to the Queen. It combines the powers of the Rook, the Bishop and the Knight, making it the most powerful piece. It's so powerful that it holds complete dominion over the entire 5x5 square centered on itself, and like the Archbishop, holds the power to singlehandedly checkmate a bare King undefended. Naturally, though, such a powerful piece tends to be quite rare in actual variants.

The Elephant

Before there were Bishops, the piece that moved diagonally was the Elephant. This was one of the very first pieces chess ever had, way back when it was called Chaturanga. It was also a lot weaker than its modern counterpart. Elephants can only jump exactly two squares diagonally. Because of this, not only are they color-bound, but they can't even reach all the squares of that color. Assuming they start on c1 or f1, like a regular bishop would, each one is limited to only ever being on one of eight squares on the entire chessboard.

Cavalier Chess

The Centaur

The Centaur is the main objective of Cavalier Chess, a variant where many of the pieces gain knight powers. It's half horse and half man, and as such, it has the powers of both a King and a Knight. (It's not necessarily royal like a King would be, but in Cavalier Chess it is.)

The Unicorn

In Cavalier Chess, this piece is actually called a Nightrider, but I decided I wanted them to be unicorns instead. The Unicorn is effectively to the Knight what the Queen is to the King. It can make any number of (2, 1) leaps in the same direction, provided each square it would pass through is empty.

My Original Creations

The Ninja

Ninjas in feudal Japan were expert hitmen and guerrillas, though their stealthy methods of combat earned them the disdain of the samurai. Here, they move like a Unicorn, but rather than capturing in the same way, they capture by stepping backwards or diagonally backwards by one square. This move is intended to represent the Ninja slaying their mark with a swift strike to the back. (Did you know? The black clothing that stereotypical ninjas wear was mostly used in Japanese stage plays, for stagehands to wear so they wouldn't draw the audience's attention.)

The Pirate

And what better rival for a ninja than a pirate? Yo ho ho! The Pirate is a master of the seven seas, but when it comes to a land battle like chess, they haven't quite gotten their land legs just yet. A Pirate can move like a Queen, but it can ONLY land on the edges of the board (i.e. the coastlines). This movement is strongest when the Pirate is in a corner square, but it has the bizarre side effect that the Pirate can cross through the board and land on the opposite coastline.

The Drunk Pawn

Some Pawns are unable to handle the hardships of war, causing them to develop a habit of drinking hard liquor. These drunkards, known to more "normal" chess variant enthusiasts as Berolina Pawns, behave exactly the opposite of regular Pawns. They stumble and stagger diagonally forward by one square at a time (or two, if it's their first move), and they capture by moving one square straight forward.

Conclusion

I have some more pieces I want to make in the future, and some that I've already made but haven't yet documented with pictures. When I do, though, I'll add them here. In the meantime, if you'd like to learn more about chess variants, you may find the Chess Variant Pages to be suitable reading material to sate your hunger for knowledge.

This post was finished on June 17, 2023 at 2:35 AM.

🎵 Battle Chess Enhanced OST - Neutral Battle